Welcome!

Posted: August 15, 2011 Filed under: Uncategorized 2 CommentsI am a wife and stay-at-home mother to one darling little girl, with a degree in Psychology and a background working with children ages 2-11. I have worked in a preschool setting as well as a private nanny. Children have and will always be one of my greatest passions, and I take great joy in seeing happy and healthy children.

In March of 2011, I gave birth to a beautiful baby girl (Sweet Pea), in my home and without any sort of labor augmentation or pain management. I credit my self-education, the support of a wonderful husband and midwife, and just a little bit of luck to my great experience. After an early pregnancy loss and fertility issues, I didn’t go into pregnancy with a lot of confidence in my body, but birth changed all that. I had a truly transformative experience, and it is now my sworn duty to guide other women toward their own metamorphoses.

Too many women in our culture are deprived of a positive birth experience by a malfunctioning medical system. Choices in birth are disappearing left and right, and new technologies fail to improve the outcomes for mothers and babies. The more I learn about our maternal care system, the more I am convinced that it is time for women to stand up and take back what is rightfully theirs — their births.

And it isn’t just in the delivery room where women are being manipulated — mothers are bombarded left and right with “advice” about raising their children. But how much of this advice is supported with evidence to be the healthiest choice for your child? Sadly, not much of it. I have explored some of the alternatives to “normal” feeding, sleeping, and discipline, three of the most volatile decisions facing today’s parents. I have had great success exploring these “variations on normal,” and believe others will as well.

I invite you to join me.

Making the Most of a Bad Breastfeeding Experience

Posted: May 15, 2012 Filed under: Practical Parenting | Tags: breastfeeding, formula, parenting Leave a commentBreast milk is the perfect food for a new baby. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that all babies be exclusively until 6 months of age, and that breastfeeding should continue until at least 2 years of age. Exclusive breastfeeding has been linked to a variety of health benefits for both mother and baby, including increased immunity, reduced risk of obesity, and lower risk of cancer and osteoporosis in mothers. Most mothers, especially in the industrialized world, are aware of the benefits of breastfeeding, and according to the 2011 Breastfeeding Report Card put out by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), nearly 75% of American babies receive SOME breast milk. But by 3 months, 65% of babies are receiving some kind of supplement, and by 6 months that percentage jumps to 0ver 85%. By 12 months, the minimum breastfed age recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), less than 25% of babies are receiving ANY breast milk. So even though it seems most mothers know enough about the benefits of breastfeeding to initiate it, the majority of them encounter challenges at some point along the way that makes it difficult for them to continue nursing their child.

So what should a mother do when she encounters such challenges? The World Health Organization has explored the various options available to new mothers who are for any reason unable to continue breastfeeding:

Mother’s Breast Milk in a Bottle

There are many reasons why a mother may prefer to pump her breast milk and bottle feed. Some mothers experience pain with breastfeeding, while others find it difficult to continue breastfeeding once they return to work. Many families do a mixture of breast and bottle-feeding in order for another adult to care for their child. This is the safest alternative to breastfeeding, since your baby still receives the natural health benefits of breast milk. However, some mothers find that exclusive pumping is in some ways even more difficult than breastfeeding, especially since pumping is the less efficient way to empty the breast, and find it necessary to turn to other supplements. Since many mothers return to work between 6 and 12 weeks, this could explain why 65% of babies are at least supplemented with formula at 3 months, or why less than half are receiving ANY breast milk at 6 months.

Another Mother’s Breast Milk in a Bottle

If a mother is unable to produce milk to sustain her child (e.g., adoption), the next alternative is giving the baby another mother’s milk in a bottle. This is possible through either private mother-to-mother donations or through a milk bank.This provides your baby with the next best nutrition, but can be inconvenient (driving all over town to pick up donations) and is definitely more expensive than formula, but mothers who choose this method consider it worth it to provide their baby with the best nutrition. Obviously, not everyone has the time and resources to feed their baby donated breast milk, in which case formula is their only remaining option.

Infant Formula in a Bottle

After considering all other methods, if a woman still finds it difficult to feed her child, the third option is of course formula. Formula is a nutritious substitute for infants not receiving breast milk, but should only be used when other more nutritious options have been explored. It is more expensive than breastfeeding or pumping, but also more convenient and socially acceptable. Formula has been linked to poorer health during infancy, including higher rates of illness, digestive problems, and allergies. Although most of these problems can be addressed through further medical care, some babies do experience life-threatening or even fatal reactions to infant formula. It is essential that if you choose to give your baby formula that you follow the necessary precautions in order to ensure your baby’s optimal health.

A forth option?

Another option not mentioned in the World Heath Organization’s list is the use of a Wet Nurse, or a lactating woman who breastfeeds other women’s children. Wet nursing used to be common, even in our own culture, and was once even a respected profession, but as breastfeeding has fallen out of public favor, so has this vocation. However, it is still possible to find women who believe so much in the power of breastfeeding that they are willing to nurse other women’s children. It may even be possible to make an informal arrangement with a friend.

However you decide to feed your baby, make sure you are doing it safely and try to mimic breastfeeding as much as possible. Breastfeeding is about more than just nutrition, it is a connection between mother and child. Bottle-fed babies should be held lovingly by the caregiver, perhaps even skin-to-skin, and interacted with just as he would be while nursing. In this way you can be sure that your are providing the best possible experience for your child, regardless of what he is being fed.

Bottle-Feeding the Breastfed Baby

Belly Basics: Ultrasound

Posted: April 26, 2012 Filed under: Evidence-Based Medicine | Tags: pregnancy Leave a commentObstetric ultrasound is the use of sound waves (sonar) to get a picture of the inside of the uterus. It can be used to date a pregnancy, determine the sex of the fetus, reveal a multiple pregnancy, and detect abnormalities or potential complications. It was first used in the 1950s, shortly after a study revealed an increased rate of cancer among children whose mothers were given x-rays during pregnancy (this was a common procedure to measure the birth canal. It increased in popularity during the 1970s, and by the 1980s was routine in many countries. [1]

What is the current practice?

In the US, it is estimated that 70% of women receive at least one ultrasound during their pregnancy. [2]

What does the evidence suggest concerning routine ultrasound?

Routine ultrasound can help doctors determine a due date, predict the weight and sex of the fetus, as well as detect multiple pregnancies, birth defects, and possible complications (such as IUGR and placenta previa). However, the actual medical benefit of routine ultrasound for many of these purposes has been challenged through research. [3]

For example, the for the diagnosis of birth defects and possible complications, ultrasound consistently has a high false positive rate, meaning that many fetuses and mothers are diagnosed with problems that don’t actually exist. [4] In many cases, palpation of the uterus has been shown to be at least equally effective at diagnosing IUGR, although even with a diagnosis there is still no effective treatment for IUGR. [5]

“Pregnant women often automatically assume that antenatal detection of serious problems in the baby means that lives will be saved or illness reduced. Knowing about the problem in advance did not benefit these babies; more of them died. They got delivered sooner, when they were smaller, a choice that could have long-term effects. All twelve babies with abdominal wall defects survived. But for the six detected on the scan, their length of hospital stay was longer and they spent longer on ventilators, though the numbers are too small to be significant. They were operated on sooner (four hours rather than thirteen hours) but the outcomes were the same.” [6]

Ultrasounds are also notoriously inaccurate when it comes to determining the due date (up to 3 weeks deviation when done in late pregnancy) [7][8] and size of a baby — in some cases more than a pound off of the actual birth weight. [9]

Ultrasound has also demonstrated an increased risk of miscarriage [10], and has even been implicated as a cause for birth defects and autism. [11] So far it is unknown how the fetus experiences an ultrasound scan.

One of the more theoretical but potentially serious risks of ultrasound is the inconsistent qualifications of the technicians and the current lack of regulations about safe use. [12]

The safety issue is made more complicated by the problem of exposure conditions. Clearly, any bio-effects that might occur as a result of ultrasound would depend on the dose of ultrasound received by the fetus or woman. But there are no national or international standards for the output characteristics of ultrasound equipment. The result is the shocking situation described in a commentary in the British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, in which ultrasound machines in use on pregnant women range in output power from extremely high to extremely low, all with equal effect. The commentary reads, “If the machines with the lowest powers have been shown to be diagnostically adequate, how can one possibly justify exposing the patient to a dose 5,000 times greater?” It goes on to urge government guidelines on the output of ultrasound equipment and for legislation making it mandatory for equipment manufacturers to state the output characteristics. As far as is known, this has not yet been done in any country. [13]

Conclusions

Despite the hopes of its inventors and supporters of its use, there is evidence to support the idea that ultrasound does not improve birth outcomes.

“There was no evidence of a significant difference between the screened and control groups for perinatal death. Results do not show that routine scans reduce adverse outcomes for babies or lead to less health service use by mothers and babies.” [14]

As with many other pregnancy interventions, ultrasound is a useful diagnostic tool, but it is unnecessary for it to be used routinely on a large portion of the pregnant population. Since birth practices (such as induction and c-section) are often based on the babies estimated due date and weight, accuracy of diagnosis is critical to the best birth outcomes for women and babies. At this time, ultrasound technology is not accurate enough to determine necessary interventions, so either we need to reconsider its widespread use or change our birth practices (or both).

Once upon a time, X-ray was considered a useful diagnostic tool during pregnancy as well, with some doctors even claiming that there were “no danger” as long as the exam was performed by a “competent radiologist.” Many women received them before it was determined that such exams caused childhood cancers. [15] Are we making the same hasty mistake with ultrasounds?

“The casual observer might be forgiven for wondering why the medical profession is now involved in the wholesale routine examination of pregnant patients with machines emanating vastly different powers of energy which is not proven to be harmless to obtain information which is not proven to be of any clinical value by operators who are not certified as competent to perform the operations.” [16][17]

Will ultrasound go the way of the x-ray? In 50 years, will new research reveal the consequences of such cavalier use of this technology?

Final Thoughts

The ultrasound scan shown above is actually mine from my first pregnancy, and before I began my research into ultrasounds, I didn’t give a second thought to whether or not the procedure was actually necessary. Like many women, I enjoyed seeing my baby every few months on that ultrasound — I found it very reassuring in the beginning of my pregnancy, since I had experienced a loss a few years before. We even went in for a “4-D” ultrasound to find out the sex of our baby, and that too was a memorable experience. That said, I don’t think I will get any ultrasounds with my next pregnancy — not because I think they’re dangerous, but because I just think they’re not necessary, and may cause some women undue stress. Knowing what I know now about the dubious accuracy of such scans, and how those results can lead to unnecessary interventions, leads me to think that most low-risk, healthy pregnant women don’t require them. So as long as I’m in that category, I’d rather be left in the dark.

Further Reading

To Ultrasound or Not to Ultrasound

Is Ultrasound Scanning During Pregnancy Worth the Risks?

Ultrasound: More Harm than Good?

Ultrasound Scans Cause for Concern

Ultrasound: Weighing the Propaganda Against the Facts

The Dangers of Prenatal Ultrasound

Resources

Born in the USA, Wagner (book)

Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth, Gaskin (book)

Practical Parenting: Cord Blood Banking

Posted: February 8, 2012 Filed under: Practical Parenting | Tags: birth, cord blood, parenting, pregnancy Leave a commentQuite simply, cord blood banking is saving the blood found in the umbilical cord for future use. Cord blood (and umbilical tissue) is rich in stem cells, which, despite their controversy, have very powerful help applications because of their regenerative abilities. Cord blood is easier to match than bone marrow, meaning it can be given to a wider variety of people. It is also considered “less invasive” than the typical bone marrow donation.

After birth, the cord is clamped and cut, severing the physical connection between mother and baby. The blood that remains in the umbilical cord and the placenta, is normally discarded as medical waste, but if you choose to bank the cord blood, it will be extracted and transported to a cord blood bank.

At a PUBLIC cord blood bank, your baby’s blood will be identified by a number, tested for quality, and then cryopreserved (frozen). Doctors search the bank for their patients and if your baby’s blood is a match, it will go toward helping that person. Donating to a public bank is free.

At a PRIVATE blood bank, your baby’s blood will only be available to your family. If you have another family member with a condition treatable with stem cells, you can set it aside for that purpose, but it will not be available for public use. You pay for this exclusivity, usually around $1-2,000, and is not covered by insurance. The Royal College of Obstetrics (RCOG) [1] , the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) [2], and American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) [3] all recommend against PRIVATE cord blood banking — unless you have a family history of a genetic disorder.

Stem cell research is changing the face of medicine, and umbilical cord blood is contributing to that transformation. Conditions we thought untreatable are now being healed, saving the lives of many, including children with terminal illnesses. Cord blood is easier to match from donor to recipient than bone marrow, meaning that your baby’s blood has a greater chance of healing someone. By donating your baby’s cord blood, you could save the life of another person, including your own family. Much like donating blood or organs, donating cord blood is giving the generous and admirable gift of life.

But this gift of life comes with a price. The donation of cord blood requires immediate cord clamping, a practice I investigated in a previous post. By donating this amazing substance to someone else, you are depriving your baby of receiving it himself. And this is some powerful stuff. Who’s life is more valuable, and who does the cord blood help more? That is the difficult decision in front of you. Rationally speaking, unless you have someone specific in mind to which to donate the blood, it is probably more beneficial for your baby to receive it, and benefit from it’s miraculous health-boosting powers himself.

“The likelihood of using cord blood in private banks has rested mostly on the odds that the donor child or a family member will require a stem cell transplant. In the United States, the lifetime probability (up to age 70) that an individual will undergo an autologous transplant of their own stem cells is 1 in 435, the lifetime probability to undergo an allogeneic transplant of stem cells from a donor (such as a sibling) is 1 in 400, and the overall odds of undergoing any stem cell transplant is 1 in 217. These figures are based on actual transplant rates in 2001-2003.” [4]

If stem cells are so powerful that they can heal these diseases in others, just imagine what that could do for your own baby. Stem cells could cure cancer — what if they could also PREVENT it? To whom would you rather give this gift, a stranger or your newborn baby? Which do you decide?

Resources

Evidence-Based Medicine: Immediate Cord Clamping

National Marrow Donor Program — Cord Blood Donation

Evidence-Based Medicine: Labor Induction

Posted: January 15, 2012 Filed under: Evidence-Based Medicine | Tags: birth, birth plan, induction, interventions, pregnancy 1 CommentArtificial induction begins contractions and dilation of the cervix, essentially starting labor before it begins on its own. Breaking the water, Foley balloons, prostaglandin gels and tablets, and IV synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin) are all methods of labor induction, with Pitocin being the most popular.

Induction was originally used to deliver babies in women with small pelvises (common side effect of Rickets, a Vit D deficiency) and in cases of pre-eclampsia. Like many medical practices, it was at first very risky, and was only done when it was more dangerous for the woman to remain pregnant than to induce. Now it is relatively safe and quite common, with over a third of all births occurring through artificial beginnings. [1]

What is the current approach to induction?

Once upon a time, obstetricians believed that prophylactic (preventative) inductions should be practiced in all pregnancies. Instead of being left at the mercy of spontaneous labor, doctors can now schedule it. And while it is (fortunately) not practiced in all labors, it is a growing trend, and can even be performed without medical indication (elective). The most common reason given for induction is “post dates,” or overdue, followed by a maternal health problem, a desire to get the pregnancy “over with,” and concern about the baby’s size. Pitocin is used in 80% of medical inductions, and most women experience more than one induction method, usually breaking the waters. [2] The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) recommends against induction before 39 weeks in the absence of a medical indication. [3]

What does the evidence suggest about induction?

Pitocin has been approved by the Federal Drug Administration as safe for use, but there is a noted increase in epidural use, interventions, and c-sections when an induction is attempted. [4] [5] However, inductions are often unsuccessful, even when combined with amniotomy (breaking the water), which may increase a woman’s chance of a cesarean section. The ideal rate, calculated by the World Health Organization (WHO) is 10%. [6]

One of the most common reasons given by women and obstetricians for inducing is when a woman is overdue or “post-dates.” Research has shown a VERY slight increase in fetal death after 41 weeks, but the absolute risk is quite low regardless. This means that the risk of the baby dying without the induction was also quite small, but induction reduced the risk further. [7] The risk increases even more after 43 weeks, but very few women ever go that long, even without induction. [8]

Another reason some pregnancies are not allowed to go beyond the due date is the fear that the baby will grow too large to fit through the mother’s pelvis. However, despite this being a common reason given for induction, there has actually been no evidence to suggest that induction due to suspected macrosomia (big baby) has any benefit to mother or baby. Also, due to the documented inaccuracy of ultrasounds for determining due date and size of the baby [9][10], induction carries the risk of the baby being premature, or at a low birth weight. [11]

What are the risks of labor induction?

Although Pitocin, one of the most common induction drugs, as well as many other methods of induction, have been proven safe to use, the dangers of induction are more about the resulting interventions that may occur as a result. For example, the stronger and more frequent contractions that happen with artificial induction cause most women to request an epidural, which while relatively safe, does carry it’s own complications. The contractions themselves may increase “fetal distress,” since the baby does not have the opportunity to recuperate between contractions, and “fetal distress” is more likely to result in an instrumental (forceps or vacuum) or surgical delivery. Again, it’s not the induction itself that causes the problem, but rather the resulting “cascade of interventions” that can follow. [12]

The unnaturally strong, long, and frequent contractions can put undue stress on the uterus, leading to higher rates of postpartum hemorrhage and uterine hyperstimulation and rupture. Women attempting a Vaginal Birth After Cesarean (VBAC) should be especially cautious about using any artificial induction methods, as they are at a higher risk of hyperstimulation and rupture [13], which can be fatal.

What is the alternative?

If at all possible, WAIT. Studies have shown that in the final days of pregnancy, your baby’s brain and lungs are still developing. Even just one day could make the difference in terms of your child’s long-term health. One current theory is that, when your baby’s lungs are ready to breathe on their own, they release a protein that triggers labor to begin. [14] Unless it absolutely essential to induce, you should try to give your baby every opportunity to develop.

Natural induction methods would also be an option, such as breast stimulation [15], acupuncture [16], or good-old fashioned nooky[17].

Final Thoughts

I am always just a little bit nervous whenever I know someone who is being induced. Too many women I’ve known have experienced C-Sections as a result, and too many babies have had complications. Just because it is possible to plan your baby’s birthday down to the hour doesn’t make it preferable to waiting for natural labor. The birth process is amazingly complex, and rushing any part of it could have short-term or even long-term consequences that we have yet to understand. You absolutely have the right to refuse induction if you don’t believe it is in your or your baby’s best interests.

Conspiracy Theory Time:

Inductions are better for business. Data from the CDC shows an increasing trend toward births occurring during daylight hours Monday through Friday, indicating that inductions are done at least partly for the convenience of the doctor. [18]

Think about it from the physician’s perspective…Let’s say you have a very busy practice, and you’re trying to have a quality of life, maybe you’ve got a young family, you don’t want to be running out every night to deliver a baby, or not coming home in time for dinner, missing everything that your child is doing. So what happens is you try to get all the births in between 9 and 5, and to do that, you have to make sure nobody goes into spontaneous labor; and to make sure of that, you have to induce them all early. Or let’s say this is the day you have to be on call, it’s best then for you to induce three or four people on that day because you can get them all done at once. Those three or four people aren’t going to call you on the weekend, they’re not going to call you in the middle of the night, they’re not going to interrupt your office hours, they’re not going to give birth at any time that’s inconvenient.

Some say scheduling births is all doctors can do to maintain their level of income while larger and larger portions of it are earmarked for malpractice insurance premiums. If a doctor misses a birth, he loses revenue. Even if an induction doesn’t work, a cesarean is waiting. And from incision to sutures, a cesarean takes less than an hour. In addition to time management, the looming fear of lawsuits drives doctors to act rather than to wait. “Doctors are practicing more defensively,” says Bernstein. It’s irrelevant that an induction might lead to a cesarean. “To be blunt, you don’t get sued when you do a cesarean,” he says. “You get sued when there’s a damaged baby. And if they can find any reason that the woman should have been delivered earlier, then it doesn’t matter whether the damage had anything to do with how you managed the baby. All that matters is did you do everything that you could have possibly done? And that causes doctors to say, `Well, it’s got to look like I’ve tried my best. And trying my best would be to deliver the baby.’ So you explain to the mother that the fluid’s a little low.

Jennifer Block. Pushed: The Painful Truth About Childbirth and Modern Maternity Care (pp. 42-43). Kindle Edition. [*]

Resources

Born in the USA: How a Broken Maternity Care System Must Be Fixed to Put Women and Children First (Wagner, 2008)

Listening to Mothers Survey (2005)

Pushed: The Painful Truth About Childbirth and Modern Maternity Care (Block, 2008)

Evidence-Based Medicine: Episiotomy

Posted: January 6, 2012 Filed under: Evidence-Based Medicine | Tags: birth, birth plan, episiotomy, interventions, pregnancy 1 CommentWhat is Episiotomy?

Episiotomy is simply a surgical cut intended to widen the vaginal opening. Its use is meant to prevent severe tears and trauma to the perineum during a vaginal birth. It can also be used to expedite a birth in the case of fetal trauma, or to allow an instrumental (forceps or vacuum) delivery. The two most common types of episiotomy are medio-lateral and midline, which basically refers to the angle of the cut — midline (toward the anus) or medio-lateral (diagonal, away from the anus). [1]

What does the evidence suggest about its practice?

More than 20 years of research indicates that episiotomies should NEVER be a routine practice [2][3][4][5], and that a restrictive policy is best. The World Health Organization recommends episiotomy rates of below 10%. [6]

What is the current practice?

The practice of episiotomy originated in the 18th century, and became widespread over the next 100 years as instrumental deliveries rose in popularity — widening the opening helped doctors maneuver the baby manually or with forceps. For a long time, it was assumed that a surgical cut was better than a natural tear, and that it reduced the chances of incontinence (leaking urine and/or feces) and improved sexual function. At some points in history, it was a routine hospital birth procedure, with upwards of 70-80% of all mothers experiencing one, with first time mothers more susceptible than others. [7]

In 1983, research showed that not only did episiotomy NOT improve incontinence or sexual function, but that it actually seemed to increase the odds of a woman experiencing BOTH. [8] The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) changed its stance concerning the procedure, encouraging its members to take more preventative measures, and avoid episiotomy whenever possible [9], but it took over 20 years for the policy to become practice. Some hospitals still have a policy of routine episiotomies. [10] In 1997, the rate of episiotomies was 29% of all births, but in 2006, the rate of episiotomy was about 9%, [11][12] just under the <10% recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). [13]

Today, its use is more restrictive, usually only performed in cases of fetal distress where a quick (usually instrumental) delivery is required. [14]

What are the risks of episiotomy?

Most of the consequences of episiotomy effect the mother, rather than the baby, and while they are generally not life-threatening, they can greatly impact her quality of life and make her birth experience more traumatic. Episiotomy increases a mother’s chance of blood loss [15] during delivery and rate of infection. [16] Women with episiotomies have a longer recovery time and experience more incontinence [17][18][19] and painful intercourse [20][21], even after the cut has healed. And, despite claims that episiotomies reduce the risk of severe tears, the procedure actually INCREASES a chance that she will tear further. [22] Think of how you might snip a piece of fabric in order to rip it in two — same concept.

Why does episiotomy increase a woman’s chances of incontinence?

When a woman is sutured after an episiotomy, the doctors are essentially sewing together her pelvic floor muscles, which are essential to bladder and bowel control, as well as sexual pleasure. Some doctors have claimed that a sutured vagina is as good as or “better than new,” but as anyone whose had a c-section or major surgery knows, sutured muscle never heals quite like new. It is weaker and looser (hence the post c-section “pooch”). This weakness, this looseness, can actually contribute to incontinence and painful intercourse, not prevent it.

Many surgeons believe a surgical cut to be better than a natural tear, although scientific data has proven otherwise. The misperception stems from the fact that obstetricians are surgeons accustomed to sewing up openings that have been made with a scalpel-that is, cuts that are straight and clean-whereas tears are ragged and irregular. It is perhaps counter-intuitive to surgeons that a tear is better than a cut. What they don’t appreciate is that a tear follows the lines of the tissue, which can be brought back together like a jigsaw puzzle. An episiotomy cut, on the other hand, ignores any anatomical structures or borders and disrupts the integrity of muscles, blood vessels, nerves, and other tissues, resulting in more bleeding, more pain, more loss of muscle tone, and more deformity of the vagina with associated pain during sexual intercourse.

Marsden Wagner. Born in the USA: How a Broken Maternity System Must Be Fixed to Put Women and Children First (p. 56). Kindle Edition.

Essentially, the natural alternative to episiotomy is tearing, although it is absolutely possible to have a vaginal delivery with neither a cut or tear. [23]

Take Action!

During pregnancy, exercises such as Kegels and squats have been shown to reduce the chances of a tear by increasing the elasticity of the perineum. Sexual activity during pregnancy has also been shown to soften the tissue, making it expand easier and with fewer tears. Perineal massage during the third trimester has demonstrated similar benefits. [24][25]

The choice of birth attendant can also make a big difference as well — Certified Nurse Midwives (CNMs) and younger obstetricians have lower rates of episiotomy. [26][27][28]

The traditional hospital birth position, either lying down or reclined, increases a woman’s chances of tearing or requiring an episiotomy due to the improper positioning of the baby’s head pressing against the perineum. [29][30]

Epidural use, because the woman cannot feel the trauma while it is happening, has also been shown to increase tearing. She also may be “coached” through the pushing phase, rather than led by her natural urges, which again increases her chances of tearing. [31]

Instrumental deliveries, such as forceps or vacuum extractions, have also been shown to increase perineal trauma.

Alternatively, laboring and/or birthing in warm water [32], squatting or side-lying positions during pushing, “breathing down” the baby during crowning, as well as the use of hot compresses [33] have been shown to reduce the chances of tearing and episiotomy.

Knowing all this, you have the right to REFUSE THIS PROCEDURE. In fact, you have the right to refuse any procedure you don’t want. Exercise that right and get the birth you want! [34]

Final Thoughts

The perceived need for episiotomy seems based in a couple faulty assumptions. First, that the woman’s body is somehow incapable of giving birth (an assumption rampant in the medical community), and therefore needs help from a doctor in order to be successful. And secondly, that a cut is better than a tear (which doctors seem to believe are an unavoidable part of giving birth). Neither of these assumptions are true, and it’s time for hospitals, care providers, and women to consider just who actually benefits from routine episiotomy.

Even though ACOG has recommended against routine episiotomy since 1983, some doctors and hospitals seem not to have gotten the memo. And it’s not just episiotomy — many practices that have no basis in evidence continue to be routinely practiced in modern obstetrics. It makes me wonder, just how much time, and how much evidence, do obstetricians and hospitals need in order to stop doing things that hurt women and babies? Recently, ACOG changed their policy regarding Vaginal Birth after Cesarean (VBAC), but I personally remain skeptical as to how long it will take before attitudes really change. [35]

The rate of episiotomy (and forceps delivery) may be down, but the C-section has risen significantly. Are we just trading one cut for another? Is that an improvement? [36]

Conspiracy Theory Time:

When you look deeply into the history of episiotomy, a surprising amount of sexism comes floating to the surface. Just like many other birth interventions, it is first based on the principal thought that women are incapable of giving birth, that they must need medical intervention. The benefits of episiotomy are questionable, but the consequences to the mother are devastating — the humiliation of incontinence, a long and painful recovery, and a loss of her ability to feel sexual pleasure. And still the advocates of episiotomy tout that one of the benefits of the procedure is “re-virginization,” which is clearly a benefit for the woman’s partner, not to the woman herself — because losing her virginity was so great, every woman wants to do it TWICE, right? Sounds like whoever came up with that line doesn’t have a vagina, if you know what I mean. Plus, the idea that the only good vagina is a tight vagina, and no man is going to want to be with someone with a used vagina, reduces the woman’s value to one part of her body, and that is blatant objectification. See, sexism at its finest.

Resources

Avoiding Tears and Episiotomies

Benefits and Risks of Episiotomy

Birth: The Surprising History of How We Are Born (Cassidy, 2007)

Born in the USA: How a Broken Maternity Care System Must Be Fixed to Put Women and Children First (Wagner, 2008)

Empower Yourself: Know Your Rights!

Episiotomy and How to Avoid It

Episiotomy: Ritual Genital Mutilation in Western Obstetrics

Ina May Gaskin’s Guide to Childbirth (Gaskin, 2003)

Evidence-Based Medicine: Immediate Cord Clamping

Posted: December 13, 2011 Filed under: Evidence-Based Medicine | Tags: birth, birth plan, cord blood, cord clamping, pregnancy 6 CommentsWhat is Immediate Cord Clamping?

During pregnancy, the umbilical cord transfers oxygenated, nutrient-rich blood from the placenta to the baby. After birth, when the baby is able to breathe on its own and receive milk for nutrition, the placenta, and therefore the umbilical cord, is no longer necessary for the baby’s survival. In the wild, many mammals sever the umbilical cord with their teeth after birth, but in the human medical setting, the cord is first clamped and then cut with medical scissors. Immediate Cord Clamping (ICC) simply refers to the timing of this clamping after birth. If the cord is clamped and/or cut less than 1 minute following birth, it is considered immediate, or “early,” cord clamping.

What is the current practice toward cord clamping?

Early cord clamping originally came into practice in the 1950s as an attempt to reduce the instance of neonatal jaundice, and was used in the 1970s to facilitate resuscitation. In the 1990s, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) called for early clamping for legal purposes. Today the procedure is routinely performed by most obstetricians, while most midwives prefer delayed clamping. [1][2]

What does the evidence suggest?

Even after 50 years of use in US hospitals, there is actually no evidence to support the routine practice of immediate cord clamping. In fact, all the available research suggests that not only does ICC show no benefit to the baby, but that it actually does damage. [3] This is because of a phenomenon called placental transfusion, where for a period of time after birth, a healthy placenta continues to supply oxygenated, nutrient rich blood to the baby. ICC disrupts this process, which can have long-term consequences for the baby (see below).

What are the risks of immediate cord clamping?

It is estimated that at least 30% of the baby’s potential blood volume is transferred by the placenta after birth [4] — which means that clamping the cord early frequently results in hypovolemia (too little blood) and anemia (too little iron). Infant anemia is linked to a variety of problems, such as cerebral palsy, respiratory distress, behavioral and developmental disorders (such as autism).[5][6][7]

“To clamp the cord immediately is equivalent to subjecting the infant to a massive hemorrhage, because almost a fourth of the fetal blood is in the placental circuit at birth.” [Windle, 1969]

Risks to the mother include an increased chance of retained placenta and postpartum hemorrhage, which can lead to some serious complications. [8]

What is the alternative?

In a word, waiting. Delaying the clamping of the cord to at least two minutes has been shown to prevent anemia during the first year of life, therefore reducing the risk of anemia-linked disorders during childhood. [10]

Although the need for resuscitation has been cited as justification for ICC, it is actually possible, if not preferable to perform resuscitation with the umbilical cord attached, since the placenta continues to provide oxygenated blood to the baby for several minutes after birth. A newborn’s lungs may not be developed enough to distribute oxygen to the body, but a healthy placenta and umbilical cord usually are. [9]

Babies delivered by cesarean, as well as premature infants, can also receive the benefits of delayed clamping. Research has found a significant reduction in infection and bleeding in the brain amongst preemies who received a complete placental transfusion. [11][12][13]

Delaying cord clamping at least two minutes is recommended by the World Health Organization. [14]

Final Thoughts

Immediate cord clamping has demonstrated no benefit to babies or mothers. In fact, research has shown that it actually does harm, by increasing the risk of anemia in infants, which can cause lifelong disabilities. The physiological norm is to wait until the cord has stopped pulsing before severing it — immediate clamping and cutting is an intervention that was put into practice without any evidence to support it. In the absence of such evidence, after 50 years of practice, isn’t it time we acknowledge that it may not be the right choice? Isn’t it time to admit that maybe Mother Nature knows better on this one?

[ http://www.nurturingheartsbirthservices.com/blog/?p=1542 /caption]

[ http://www.nurturingheartsbirthservices.com/blog/?p=1542 /caption]

Conspiracy Theory Time:

A large portion of the evidence to support delayed cord clamping has come from midwives, who have continued to practice it even as doctors advocated for immediate clamping. Ever since birth moved from the home to the hospital, and from doctors to midwives in the early 20th century, doctors (for the most part) have viewed themselves as more of an authority on birth than midwives. Could it be that doctors (as a group) have resisted the evidence in support of delayed cord clamping simply because it came from midwives? How much of this practice is because of evidence (of which there is none) and how much of it is simply defending their egos? Is the pride of doctors worth more than the health of American babies?

One of the conditions linked to immediate cord clamping is autism. Evidence suggests that babies delivered by obstetricians (more likely to perform ICC) have higher rates of autism than babies delivered with midwives (more likely to delay clamping/cutting). [15] What if this condition could be prevented simply by waiting an extra minute or two before clamping the cord?

Since immediate cord clamping became routine in many hospital settings, birth has become more and more medicalized. Interventions such as induction and labor augmentation have led to more diagnoses of fetal distress, as well as a higher rate of cesarean deliveries. Another change in fetal medicine since the introduction of ICC is the increasing rate of pregnancies resulting from fertility treatments. These pregnancies are more likely to result in multiples (and therefore higher likelihood of c-section) and prematurity [16], both of which increase a baby’s risk of requiring resuscitation. Premature, “fetal distress/asphyxia” diagnoses, and babies delivered via c-section all experience higher rates of resuscitation. Luckily, perinatologists have become more and more adept at saving these “at risk” babies, but what if there were fewer babies to save? What if doctors and women made decisions about their pregnancies and births based on evidence, and used fewer interventions? What if we took a proactive approach and made the decisions that would lead to healthy babies in the first place, rather than relying on resuscitation and other life-saving measures simply because they are available?

Take Action

Most newborn procedures can be delayed or done while the baby is held by the mother, reducing the need to clamp/cut the umbilical cord. Even in the case of problems at birth, it is possible that the natural transfusion between placenta and baby could benefit the baby. Obstetricians seem to be more likely to ICC than midwives, so keep that in mind when you choose your care provider.

Resources

5 Good Reasons to Delay Clamping the Cord

Delayed Cord Clamping Should be Standard Practice in Obstetrics

Ina May Gaskin’s Guide to Childbirth

Late vs Early Clamping of the Umbilical Cord in Full-Term Neonates

Long-Lasting Neural and Behavior Effects of Iron Deficiency in Infancy

Evidence-Based Medicine: Continuous Electronic Fetal Monitoring (EFM)

Posted: December 5, 2011 Filed under: Evidence-Based Medicine | Tags: birth, birth plan, efm, electronic fetal monitoring, interventions, pregnancy 2 CommentsWhat is Electronic Fetal Monitoring (EFM)?

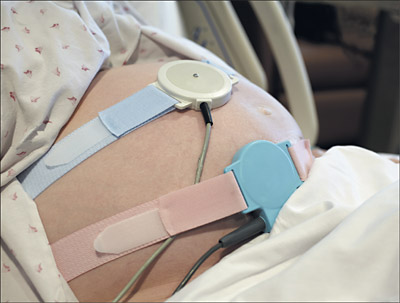

EFM monitors the baby’s heart rate and the mother’s contractions during labor, and alerts medical staff to any distress. The most common method of EFM is placing two receivers, held in place with two elastic belts, on the mother’s abdomen. A less common form of EFM involves inserting a receptor into the baby’s scalp.

EFM was originally intended for use in high-risk patients, and was thought to reduce fetal death and brain damage, including cerebral palsy and retardation due to oxygen deprivation. [1][2]

What does the evidence suggest about its practice?

Despite numerous studies on the matter, no benefit has been found from the routine use of EFM technology. [3][4][5] There has been no reduction in infant deaths or cerebral palsy, which was the technology’s intended (and advertised) benefit. [6] Because of this, as well as the documented risks of the practice, both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) recommend against continuous electronic fetal monitoring. [7][8] The technology has never been reviewed by the Federal Drug Administration for safety or efficacy. [9]

How is EFM currently used?

EFM is currently used in almost every birth in the United States, as much as 93% of the time. Some hospitals require at least a 20-minute observation upon admission to check the health of the baby. [10]

What are the risks?

Continuous use of EFM has repeatedly been linked to higher rates of intervention, including instrumental delivery and c-section, which carry their own set of risks. [11] There is a slight increase in the rate of infection to the baby, especially when an internal monitor is used, but these are typically mild and easily remedied. The patterns on the print out are open to the interpretation of the hospital staff, which frequently leads to misdiagnoses (this is called a “high false positive rate,” and is a sign of unreliability). [12]

In addition to its questionable benefit and documented risks to both mother and baby, the use of EFM has been shown to reduce the quality of care — women complain that the machine becomes the central focus of medical staff and birth attendants, rather than the laboring woman herself. Movement can cause the machine to malfunction, so the woman is confined to labor in bed on her back, a position that is shown to be more painful and less effective for labor to progress.

What is the alternative?

Intermittent listening with a Doppler or fetoscope has been shown to be just as effective at detecting fetal distress as constant monitoring, while at the same time reducing the risk of instrumental delivery and c-sections due to a “fetal distress” diagnosis. [13] This is the method recommended by the World Health Organization.

Final Thoughts

Electronic fetal monitoring has been accepted as a normal part of maternity care in the United States, despite any evidence of its benefit to the laboring woman and her baby. And while it provides the appearance that an individual is receiving continuous care, it has in fact made it possible for medical staff to care for more patients simultaneously, meaning a lower standard of care for each patient. Its high false positive rate means that more women are being subjected to unnecessary interventions and surgery because of the misdiagnosis of “fetal distress.” By confining women to bed, EFM makes labor more painful and less effective than if the woman was allowed freedom of movement. Despite claims that it would improve outcomes for mothers and babies, EFM has repeatedly shown NO benefit to either, after 30 years of research. So WHY IS IT STILL BEING USED??

Conspiracy theory time:

EFM has become so normalized that it is frequently used as evidence in malpractice lawsuits, which is why many hospitals now mandate its use — it is their paper trail. [14] EFM gives the illusion of accuracy, but is in fact open to interpretation much of the time, hence its high rate of inaccuracy. Without it, doctors and hospitals would be more vulnerable to lawsuits, but with EFM they can justify their choices.

EFM is a multimillion dollar technology, whose makers implied that a perfect outcome was possible with its use. Its widespread adoption reduces costs to hospitals by making it possible to care for more laboring women simultaneously, but the resulting interventions (such as c-section) actually make birth more expensive for patients. Is it possible that those that stand to benefit financially (the EFM industry and the hospitals that use it) are pushing for its continued use? Is it possible that these groups are more concerned about their bottom line than what is best for you and your baby?

Take Action

You have the right, as a patient, to refuse any procedure, including EFM. You can request intermittent monitoring instead, which has been shown to be just as effective in detecting problems, but without the associated risks. You can choose a care provider that prefers a less technological approach, or give birth in an environment where EFM is not routinely used, such as a birth center or at home. You do not have to accept any risk you are not comfortable taking. Take your birth into your own hands — know your rights and know your limits.

Resources

Born in the USA: How a Broken Maternity Care System Must Be Fixed to Put Women and Children First (Wagner, 2008)

Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth (Gaskin, 2003)

Listening to Mothers Survey (2005)

Pushed: The Painful Truth about Childbirth and Modern Maternity Care (Block, 2008)

Practical Parenting: Circumcision

Posted: November 19, 2011 Filed under: Practical Parenting | Tags: circumcision, parenting 3 CommentsThere is a lot of false information going around about circumcision — that it’s important for proper hygiene, that it lowers the risk of contracting STDs, that the infant can’t feel it or that it carries no risk of injury or death. Parents make this decision for their child based on this misinformation, but when things go wrong, their sons are the ones who get hurt.

Circumcision, for those unfamiliar with the term, is the removal of the foreskin, a piece of skin which covers the head of the penis. The head, or glans of the penis has a similar function to the female clitoris, so the foreskin is similar to the clitoral hood in women — one of it’s functions is to protect the highly sensitive glans. The foreskin itself also serves a sexual function — the highly sensitive nerves found in the foreskin can enhance sexual pleasure, not only for the man but for his partner as well. Nearly a third of baby boys are circumcised shortly after birth, and in the Jewish culture it is considered an essential rite of passage. Most American women have never seen a circumcised penis.

Here are some of the more common reasons parents give for circumcision:

Reason #1: Circumcision is important for hygiene.

This is essentially saying that the vagina would be easier to keep clean if it weren’t for those pesky labia. That may be true, depending on your definition of clean, I guess. Lots of things would be “easier to keep clean” if we simply removed a part of our body — ears, bellybuttons, nostrils, between our toes — but instead of removing it, we simply learn how to clean around it. What a concept.

Reason #2: If he is intact, he will be teased.

This may be very true. He might also be teased if he has red hair, or freckles, braces, glasses, is fat, is learning disabled, is gifted, has a lisp, has a unique name, is gay, stutters….

Kids can be cruel. Cutting off a perfectly healthy part of his body doesn’t make him any less tease-able, I’m afraid.

Reason #3: It’s better for his health.

Once upon a time, circumcision was claimed to reduce chances of a boy contracting HIV and other STDs, as well as reducing his chances of getting penile cancer. These claims have recently been disproved. The best thing a man can do to prevent HIV, STDs, and penile cancer is to practice safe, non-promiscuous sex — cut or uncut.

Reason #4: He can’t feel it anyway.

Please tell me you don’t believe this. Can he feel when he gets a shot? Can he feel you touch him? To think that he can feel everything else but not someone cutting off a piece of his body is just ludicrous. If someone tells you this, please just laugh in their face.

Here are my thoughts on circumcision:

1. It’s cosmetic, therefore technically unnecessary.

2. It carries some risk.

Less than 1% of boys who undergo circumcision will either during or after the procedure. I mean, that’s still about a 99% chance they won’t, so the risk isn’t HORRENDOUS, but if there’s no health benefit, and arguably no social benefit, is there any reason to take the risk?

And even if they don’t die, what if they botch it? I once heard the story of a man who realized during puberty that he had a botched circumcision, when the skin of his penis wouldn’t stretch enough during an erection. Ouch. What would you rather your child endure — some teasing in the locker room, or learning to associate arousal with pain? Oh, and one rejected skin graft later, this man is now without a penis entirely. But hey, at least he didn’t get penile cancer, right?

Or in the 60s, when some doctors took a little bit too much off the top and cut off the penis entirely. Luckily they convinced the baby’s parents to raise him as a girl, so nobody was any the wiser. I’m sure that ended well.

My point is, if there was some actually benefit to it, 1% could be an acceptable risk. But if it carries absolutely NO benefit, why chance it?

3. Whose choice should it be?

What’s the rush, anyway? Why do we circumcise as infants? Couldn’t we just let them make the decision for themselves when they’re old enough to understand it? Are we afraid they wouldn’t make the choice we want? This isn’t like getting a little girl’s ears pierced — foreskins don’t grow back. If he doesn’t like it, he’s pretty much stuck with it.

4. It’s becoming more popular.

If you are considering circumcision because you are afraid of locker room or lover’s lane (Eek! An uncut penis!”) drama, rest assured that circumcision rates are actually plummeting in the last decade. Over two thirds of all boys born in the US in 2010 were uncircumcised. So, there might be more intact penises gracing the locker rooms, and any lovers may be more accustomed to the sight as well.

I don’t care if you circumcise or not. There’s not a HUGE risk, after all. Just know that you can’t believe everything you read on the internet — an uncircumcised penis can be just as healthy as a circumcised one. Rather than cut him, teach him how to care for himself, practice safe sex, and let him know that if he ever wants to change it, it’s his body and his choice. Armed with that knowledge and power, he can have a very happy penis. And isn’t that what we all want for our little boys?

Evidence-Based Medicine: VBAC vs Repeat Cesarean

Posted: September 29, 2011 Filed under: Evidence-Based Medicine | Tags: birth, C-Section, interventions, pregnancy, VBAC Leave a comment“Once a c-section, always a c-section.”

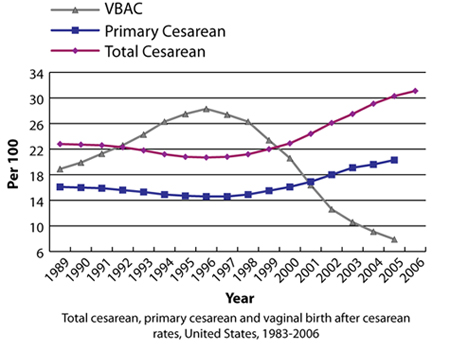

Every day, across American, millions of women face this “reality.” For the last decade, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) has supported this sentiment through its policies discouraging VBAC (vaginal birth after cesarean). But what many women and their doctors view as an unfortunate (and unavoidable) side effect of the growing c-section rate is in fact something that 60-80% of women can avoid.

VBAC became very popular during the late 1980s and early 90s, as an attempt by women to regain their birth experience from the then all-time high cesarean rate of about 24%. Many women were able to experience vaginal birth during this time, but obstetricians noticed a disturbing rise in the rate of uterine rupture, a phenomenon that is a life-threatening emergency to mother and baby. It was especially prevalent among VBAC mothers, whose cesarean scars caused weak spots in the uterine wall.

Because of this troubling observation, in 1999, ACOG issued a recommendation to its members that VBAC only be attempted in a hospital where an obstetrician and anesthesiologist were consistently present. Since women insisted on VBACs, and VBAC seemed to cause uterine rupture, the idea was to be prepared for the emergency. But what ACOG failed to address was the relationship between the routine use of induction drugs on VBAC patients, which caused hyperstimulation (harder and more frequent than natural labor contractions), thus leading to uterine rupture along the cesarean scar. So rather than dealing with one of the causes of the problem and discouraging unnecessary inductions (especially with off-label drugs like Cytotec), ACOG decided to instead deal with the fallout of such imprudent practices.

BUt while ACOG and its members crusaded against VBAC, striking the fear of uterine rupture into the hearts of pregnant women, they failed to educate women on the risks of the only other alternative – repeat cesarean. By doing this, they made it impossible for the women in their care to make an informed decision as to what was best for their baby. If you were given the choice of vaginal birth, with an “increased risk of uterine rupture,” and could lead to hysterectomy, fetal brain damage, or death, or a repeat c-section, which would you choose? This imbalanced attitude toward educating patients persists with many obstetricians today.

The truth is, repeat cesarean has its own risks, which are frequently downplayed by ACOG and its members.

For the mother, risks of repeat cesarean include:

- Physical problems for the mother, including hemorrhage, blood clots, and bowel obstruction (caused by scarring), infection, long-lasting pelvic pain, and twisted bowel.*

- Longer hospital stay, with an increased risk of being re-hospitalized.*

- Negative impact on bonding and breastfeeding due to separation during the critical first few hours after birth.*

- Placenta Previa** – the placenta attaches near or over the opening to her cervix; this increases her risk for serious bleeding, shock, blood transfusion, blood clots, planned or emergency delivery, emergency removal of her uterus (hysterectomy), and other complications.

- Placenta Accreta** – the placenta grows through the uterine lining and into or through the muscle of the uterus; this increases her risk for uterine rupture, serious bleeding, shock, blood transfusion, emergency surgery, emergency removal of her uterus (hysterectomy), and other complications.

- Fertility problems**

- Ectopic Pregnancies** – the egg implants somewhere other than the uterus.

- Placental Abruption** – placenta detaches before birth

For the baby:

- Breathing problems at birth*

- Increased risk of asthma during childhood*

- Prematurity**

- Low birth weight**

- Physical abnormalities or injuries to brain or spinal cord**

- Death before or shortly after birth**

* These risks are associated with cesarean section in general, not just repeat procedures, but the overall likelihood of experiencing such complications increases with each subsequent surgery.

** These risks are more common in repeat cesareans than with vaginal births, and have been shown to increase in frequency for each subsequent surgery.

[Source: Childbirth Connection]

Last year, ACOG changed its tune, lifting the restrictive recommendation. But a decade of anti-VBAC sentiment has left its mark. Because of the “increased risk of uterine rupture” that ACOG has repeatedly emphasized, insurance companies have become reluctant or even unwilling to cover the procedure. An obstetrician who would like to offer VBAC may be hesitant when faced with increased malpractice insurance costs. In some states, home-birth midwives and alternative birth centers are forbidden to offer the option. Some women have turned to home VBACs because they were unable to find a provider willing to offer it, and decided they’d rather take the risk of an unassisted home birth over a mandatory c-section. It remains to be seen how the new ACOG recommendation will affect the choices of women as to how (and where) they give birth.

Let’s hope it’s for the better.

For more information on the safety of repeat cesareans and VBACs:

Born in the USA: How a Broken Maternity System Must Be Fixed to Put Women and Children First by Marsden Wagner (2008)

Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth by Ina May Gaskin (2003)

Evidence-Based Medicine: Are Inductions Safe?

Posted: September 12, 2011 Filed under: Evidence-Based Medicine | Tags: birth, birth plan, C-Section, induction, interventions, pregnancy Leave a commentA couple weeks back, I researched the necessity of labor induction. I learned that, according to the Listening to Mothers Survey from 2005, about 40% of all labors are medically induced. I also learned that, according to birth experts Ina May Gaskin and Marsden Wagner, induction is only medically indicated in about 10% of births. This means that about three-quarters of all women who are induced are doing so without medical indication. If induction is perfectly safe, there would be no concern — so what does the research say?

The stats…

80% of medical inductions were done using a drug called Pitocin, a synthetic oxytocin, which causes the uterus to contract. Other methods of induction include prostaglandin medications applied to ripen the cervix, stripping/sweeping the membranes, and “breaking the water” (artificial rupture of membranes (AROM)). Most mothers included in the survey were subject to 2 or more methods of induction, the most common combination being Pitocin and AROM.

Not only are many labors medically induced, but many are also augmented using the same methods listed above. When these numbers are included, about 50% of women are given artificial oxytocin to either induce or augment labor, and 65% have their water broken.

The risks…

- More painful labor — Common induction methods such as artificial oxytocin can lead to longer and stronger contractions that are closer together. This means more pain for the mother during contractions, as well as a shorter period of time between contractions to recuperate. This can quickly exhaust a laboring woman, not to mention tarnish her birth experience. Many women whose labors are induced or augmented find an epidural to be a necessity.

“I went into labor on my own with my daughter, but was induced with my son. With my daughter, I found that sitting in a warm bath made the pain very manageable, and I didn’t get the epidural until very late — 7 cm, I think. With my son, I got an epidural at 3 cm — I just couldn’t stand the pain.” — Annie, 31

- Prematurity — Miscalculation of due dates can lead to a woman being induced before her baby is mature. Iatrogenic (doctor-caused) prematurity is on the rise, and with it comes all the risks commonly associated with prematurity, such as breathing problems. New research shows that the production of fetal lung proteins trigger labor — meaning that the baby triggers spontaneous labor when its lungs are ready to breathe. Inducing without medical indication means your baby may not be totally ready to breath independently. Labor should NEVER be induced before 39 weeks for this reason, and should ideally be around 42 weeks as long as the baby shows no signs of distress.

- Fetal Brain Damage or Death — The only time a fetus can get oxygen is during the rest period between contractions, so when those periods are shorter, the fetus gets less oxygen. Lack of oxygen is associated with an increased risk of brain damage.

- Maternal death — According to Marsden Wagner’s book Creating Your Birth Plan, induction of labor is linked to higher rates of uterine rupture and amniotic fluid embolism (AFE), both of which are rare but usually fatal (80% of AFEs are fatal — 50% within the first hour after symptoms appear). C-Section dramatically increases the incidence of both. Many women who survive uterine rupture undergo hysterectomies and are unable to have any more children, and most that survive AFEs are severely brain damaged. Fetal death is also common with both of these complications.

- “Cascade of Interventions” — A woman who is either induced or has her labor augmented artificially is at an increased risk of instrumental (forceps and vacuum-assisted) and surgical (c-section) interventions. So even if the induction drug itself is considered safe (which Pitocin is), the risks associated with all other forms of intervention must be calculated as well. While the more severe risks (uterine rupture, AFE, fetal brain damage) are relatively rare, the so-called “cascade of interventions” is fairly common. A woman who is induced more than doubles her riskof having a C-Section. A woman who goes in to be induced may find her plans for a low-intervention birth go awry very quickly.

“I got induced at 41 weeks because they thought she was going to be too big too birth otherwise. First came the Pitocin, then the epidural for the increased pain, which meant I was tethered to the bed with IVs, so I couldn’t move around. Then my labor slowed down, and they broke my water to speed things up. I went into labor thinking that I could manage an induction naturally, but instead I ended up with a C-Section because of failure to progress.”— Silvia, 26

- Interferes with Bonding/Breastfeeding — Artificial oxytocin alters the mother’s natural hormones during and after birth, potentially affecting her ability to bond with or breastfeed her baby. Any other interventions she experiences (such as cesarean) can also interfere.

“When my son was born, I felt like he belonged to someone else. I kept waiting for that overwhelming feeling of attachment I knew I was supposed to feel, but it just didn’t come — I felt like I was just going through the motions for weeks.” — Patty, 29

What is the alternative?

So if induction carries with it the risks listed above, it could be argued that elective induction is not in the best interest of the mother or baby. So what’s the alternative? Well, waiting. Just remember, every day your baby “cooks,” s/he will be a little bit stronger, a little bit healthier. As we talked about last week, babies can and have been (vaginally) born past their due dates perfectly healthy. Trust your baby, and trust your body to go into labor on your own — it’s better for both of you!